This is the story of how a little company from New Zealand grew to become a 14 billion dollar giant, the signs that indicated a big future ahead, and the tale of one of the greatest blunders in Australian business history. It is also the story of how we can apply the principles of what I call monster hunting to our own investing, and use the lessons on our quest to find the next potential winner while it is still small and undiscovered.

The Monster next door

I first purchased my shares in a2 Milk (ASX:A2M) in late 2015. It’s been a fun ride. In just four and a half years the shares have delivered a 2,200% return for shareholders. In annualised terms that is an incredible 99% per year. Past performance is no guarantee of future returns, both for our stock selection, and the business itself. Also, as we’ll talk about later it’s been a wild ride too. Holding on required enduring multiple occasions where the share price slumped, up to 30% or more, sometimes for more than a year.

It’s no secret that A2 Milk has generated strong returns for long-term shareholders. Bloomberg even named it as the best performing stock in the world:

It may have been the decade of smartphones, on-demand everything, and Instagram memes, but the prize for the world’s best-performing stock in the MSCI World Index goes to a dairy company in New Zealand.

But what a lot of this coverage misses is an understanding of how the company did it. A2 Milk is my favourite applied example of monster hunting. It’s not because of the returns (although sure, those are nice too). It’s because of how the business delivered those returns.

This was a company that could be purchased at multiple times throughout its growth journey for a very reasonable price. Its business is simple and its customer value proposition is easy to understand. Most of all, the returns were not driven by price swings, they were primarily driven by astounding organic earnings growth.

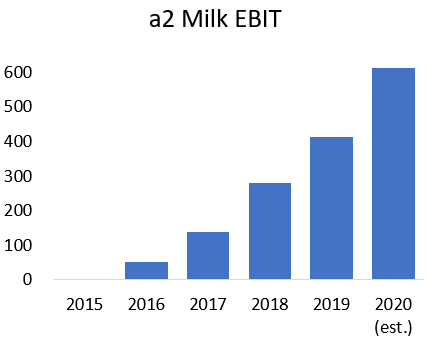

When I first purchased shares in late 2015, the total market capitalisation of the entire company was approximately $560 million NZ dollars (note: for simplicity I will refer to NZ dollars throughout this article unless otherwise noted). In 2015, a2 Milk had recently tipped past break-even and was generating $1.2m of EBIT from $155m of revenue.

Fast forward to today and the business is forecast to generate $560m of EBIT this year. Approximately the same as the company’s entire market cap in 2015. Revenue is now forecast to be $1.725 billion at the midpoint of guidance. Not only that but the company now holds $618m of cold hard cash and has another $260m worth of listed investments in its supplier Synlait Milk (ASX:SM1) representing a 19.84% stake.

In five years a2 Milk increased its revenue by 1,000%, its operating profits (EBIT) by 46,000%, and now holds significantly more cash than its starting market cap.

A2 Milk exemplifies what we should be trying to achieve as investors. Finding the large dominant businesses of tomorrow while they are still small. Luck plays a role in every business success, but this wasn’t a speculative lotto ticket like a mining explorer or biotech. This was a hyper-growth consumer brand that delivered eye-watering returns from consistent and steady improvements in fundamental performance.

What’s more, these stellar returns were primarily driven by fundamental growth, not by a big increase in the multiple that investors are willing to pay. This is best illustrated by this chart of the forward p/e multiple that a2 Milk has traded at over the past five years:

Despite many commentators saying that a2 Milk was overvalued along the way, it has typically traded at a fairly reasonable valuation given the incredible growth that it is experiencing. This is not a story of a huge multiple expansion, it is a story of compounding high returns on invested capital.

How to Catch a Monster

As I wrote in How to Catch A Monster, while most of the market is mired in mediocrity, there is a small group of companies that generate insane returns for shareholders. I call these companies monsters for the way they dominate their industries and transform portfolios. A few years ago I set out to study these huge monster winners, reading books like ‘100 to 1 in the Stock Market‘ and trawling through Standard & Poors data to see if I could identify any common traits. Most importantly, I wanted to see if it was possible to identify these winners early, before they started their huge run, and the rest of the market caught on.

As I see it, there are four steps to catching a monster:

- Choose your hunting ground – avoid pretenders to the monster throne.

- Catch your monster – identify key traits.

- Watch closely – continuously monitor and sell quickly if your thesis is broken.

- Hold on – be able to stomach the volatility without selling too early.

We’ll step through each in turn, in the context of a2 Milk.

The Hunting Ground

Investing is an art of negative space. What you don’t buy is at least as important as what you do. The best investors say no to potential ideas early and often. As I wrote in The Bizarre, Weird and Beautifully Inefficient World of Aussie Small Caps it means saying no to a lot of companies. Thousands of companies in fact. But that process of elimination leads us to a precious few companies with very attractive underlying economics.

What made a2 Milk so special – and what most of the market missed – is the power of its business model.

At first glance in 2015, a2 Milk looked like just another commodity food producer. At that time the significant majority of its revenues were from fresh milk sales at supermarkets in Australia. Its now famous infant formula had only just started to take off.

What really set a2 Milk apart is that it isn’t really a food producer at all: A2 Milk is a marketing business. All of a2 Milk’s products are produced by external suppliers that the company holds a close relationship with, in particular the New Zealand dairy company Synlait Milk. A2 Milk’s job is to create demand, maintain customer relationships, and manage the supply chain. Their partners do the hard work of building out factories and converting cow herds to be able to supply a2-protein-only milk.

As a result, A2 Milk is incredibly capital light with high returns on incremental invested capital. The company expanded from selling $136 million worth of products in 2015 to over $1.7 billion today. How much did a2 Milk spend on capital expenditures over the past five years, while it added over $1.5 billion in revenue? A paltry $9 million dollars. How is that possible? Their partner Synlait Milk did the heavy lifting for them, investing over $560 million on capital expenditures over the same period. Synlait has other customers than just a2 Milk of course, but it gives some sense of the scale of capital-intensive investment that a2 Milk avoided.

The real cream (sorry) in a2 Milk’s business model is the combination of being capital light with the premium margins that it generates as a trusted consumer brand. Once a customer has selected a2 Milk’s products, particularly its infant formula, they are reluctant to switch. As anyone who has tried moving their infant away from a formula that they are happy with knows, there is a big downside risk (tears, sleepless nights) for very little payoff. This loyalty gives a2 Milk the ability to earn an incredibly healthy operating profit (EBIT) margin of 32%. When we roll together limited capital costs, sticky customer relationships, and strong pricing power, a2 Milk generates a mouth-watering return on equity of 42% – and that’s while sitting on over $600m of cash.

As I wrote in How to Catch a Monster:

Monsters are businesses that deliver huge shareholder returns by compounding high returns on invested capital. These businesses generate strong free cash flows, and most importantly, the business is able to reinvest those cash flows at high rates, and for a very long time. That reinvestment has a compounding effect over time, with the company’s value building up faster than a snowball rolling downhill.

Running down the list of everything else that I look for, a2 Milk has extremely high-quality earnings, a rock-solid balance sheet, strong demand and supply side competitive advantages, incredibly attractive unit economics, unknown or misunderstood by the market, and is well led. Meanwhile the business was also tipping past some fundamental inflection points that I’ll touch on in a moment as well.

Safe to say that a2 Milk was, and is, very much the type of business model that we are hunting for. Now, on to Step 2.

Catch your Monster

Every monster is different, but I have found there are four key traits that monsters tend to have at the start of their journeys:

#1: They start out small

This might be an obvious one, but it’s important. It is much easier for a company to increase in value by many multiples, if it is starting from a low base.

A2 Milk started this epic run from a market cap of around $560m, much smaller than the big blue chips that get most of the market’s attention.

#2: Unique edge

A lot of people got this wrong about a2 Milk. They thought that the company’s unique edge was that it was selling a particular type of dairy protein. This confuses the raw materials with the product. The value add for any brand isn’t its raw ingredients, it’s the associations that are formed in the minds of its customers. Red Bull doesn’t just give its customers caffeine – there are much cheaper caffeine pills that do that – it gives them wings. Consumer wellness products are the same: brands first, and health products second.

By 2015 a2 Milk had a strong and steady market share of around 10% of the entire Australian fresh milk market. But most importantly it had positioned itself as the premium branded alternative to home-brand milk. For a lot of Australian consumers it was trusted as a healthier alternative. That set the scene for what would become a2 Milk’s home run product: infant formula.

In 2008 hundreds of thousands of Chinese infants were fed infant formula that had been poisoned by the industrial product melamine – the stuff that we make those shiny white table tops out of. It was a devastating scandal, with over 50,000 infants hospitalized and at least six killed. Chinese food safety standards were not up to par, so wealthier Chinese mums sought out trusted overseas brands.

Over the following years, demand for high-quality internationally-sourced infant formula soared in China. Australian supermarket shelves were often stripped bare as Chinese personal shoppers – daigou – bought all that they could and then on-sold the products in China at much higher prices.

It was against this backdrop that a2 Milk launched its infant formula product and leveraged the success in the fresh milk category. The Aussie mums that were used to buying a2 Milk’s premium fresh milk now started buying the infant formula. The product was priced significantly above competitors, and supply was tightly managed. This provided a powerful signalling effect to Chinese mums that only wanted the best for their children: the health-conscious and more affluent Australian mums were buying a2 Milk so they should too. The strategy worked and a2 Milk infant formula rapidly became the market leader in Australia.

A2 Milk is also, in its own way, a disruptive innovation. The large dairy incumbents struggle to launch an a2 protein only product and market it aggressively because by doing so they would risk hurting the image of their much larger existing traditional dairy business. It poses a fun twist on the classic innovator’s dilemma and it meant that once established a2 Milk was largely left to own the a2 protein category.

Whatever your personal take on a2 Milk’s wellness benefits, millions of people love the product — and that is what counts. A2 Milk’s unique edge was the power of its consumer brand, sticky customer relationships, and then the ability to use its growth to fuel more marketing spending, turning the flywheel even faster.

#3: Superior Management

A2 Milk’s management team have executed very well on a number of important fronts. The most important of which was management’s ability to build and maintain the premium brand position of the product.

A2 Milk’s management team often described their strategy around the supply chain as ‘keep the channel hungry’. This meant ensuring that no one distribution channel or partner ever had surplus supply that might lead them to discount a2 Milk’s products and thereby tarnish the premium positioning of the brand. Just as the owner of any expensive nightclub knows, you always want to keep a line waiting at the front door.

Management also continued to invest heavily in marketing and distribution. Almost every earnings release saw the company post incredible results, but also partially disappoint analysts by flagging another big step up in marketing spend. Meanwhile the company also built out its direct selling strategy into Chinese Mother and Baby stores – thereby building another major distribution channel and reducing reliance on daigou shoppers.

#4: Misunderstood

Finally, to have a chance of being a huge multi-bagger winner the company needs to start off being misunderstood by most of the market. The only way for a company to be significantly undervalued is for most of the market to not understand what the business is truly worth.

Whether it was the business model, or its unique edge, or the power of the brand, a2 Milk has been significantly misunderstood throughout it’s journey.

The fundamental inflection point

All of those traits were incredibly important to the purchase decision. In a2 Milk’s case it also ticked another box that I love to see before I purchase: it was just tipping past several fundamental inflection points.

In late 2015 the Australian Financial Review released an article that included a chart of pharmacy sales data. It showed that a2 Milk had, in just a few months, rapidly taken market share and was gaining ground quickly.

As I wrote in The Hidden Power of Inflection Points, there are several different types of fundamental inflection points that I like to look for. The updated pharmacy data showed that a2 Milk was tipping past not just one, but four:

- A new fast growing product/segment, ideally whose early growth has been hidden by a larger flat or declining segment

- A major demand side break-through such as a new distribution agreement

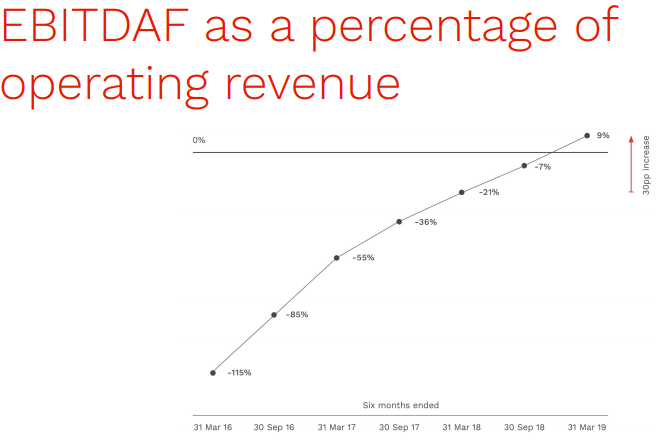

- Growth company tipping in to profitability (with strong operating leverage)

- Hyper-growth company that has just ‘crossed the chasm’ (a topic for another update)

The infant formula product was experiencing explosive hyper-growth thanks to the new distribution channel of daigou shoppers. The demand for a2 products as a category had crossed the chasm from early adopters into a mainstream segment. The growth in infant formula was being partially obscured by the slow and steady fresh milk segment. Finally, a2 Milk was just tipping in to profitability with strong operating leverage – laying the foundation for the spectacular operating profit growth that ensued.

A lot of finding monsters is about spotting anomalies and then digging deeper. I often wonder how many other people read the same article that I did in 2015 but couldn’t put it into the context of the incredible value creation that a2 Milk was about to deliver. It’s rare for a business to be hitting one inflection point, let alone multiple points simultaneously.

When you find one it’s time to pounce.

3) Watch Closely

The price of catching monsters is eternal vigilance. The next step is to clearly articulate your thesis at the time of purchase and then regularly review that thesis as new information comes to hand.

For a2 Milk that meant a big focus on how it was managing its supply chain. There was the constant threat of simply running out of stock – so we were continuously checking supermarket stores to make sure that there was adequate supply. But also, as management said, we wanted to make sure that the channel was ‘kept hungry’ and that there was no large glut of supply that might lead to discounting.

One other method that we stumbled upon after many hours of staring at tins of formula was that we could track the production and expiry dates on tins to keep track of how quickly the stores were turning over the product.

There were plenty of other things to watch along the way too: China’s forever shifting regulatory framework, larger competitors entering the market, the dependence on the manufacturer Synlait, and the role of the large e-commerce platforms in China to name just a few.

As I wrote in The Selling Blind Spot we need to be prepared to sell quickly if our thesis is broken. But if it is not, then we need to have the patience to hold on.

Hold on

“To make money in stocks you must have ‘the vision to see them, the courage to buy them and the patience to hold them’. Patience is the rarest of the three.”

100 TO 1 IN THE STOCK MARKET AUTHOR THOMAS PHELPS

Holding on requires enduring the pain of seeing your company’s share price fall and fall, and maintaining the conviction that it will come out the other side stronger.

This is what I like to call a ‘pain chart’ for a2 Milk. This chart shows when, and by how much, a2 Milk shares were below their all-time high. (Periods at 0% show when shares hit a new all-time high). Remember, this was during a period when shares increased more than 2,200%:

There have been five times when a2 Milk’s share price fell 20% or more. And on three occasions the shares fell by 30% or more. In most instances, it took a long time before the share price made it back above its previous high. To enjoy the monstrous gains to date, shareholders needed to avoid giving in to fear and selling out during those troughs of despair. It’s also a challenge to hold when the shares are soaring higher. As I wrote in The Selling Blind Spot if the shares run a little ahead of our intrinsic value estimate the smart move is often to trim the position, rather than to sell out entirely.

It is easier said than done. At the start of this article I said that this story would include one of the greatest blunders in Australian business history, here it is. In late 2015 Freedom Foods (ASX:FNP) had a close partnership with a2 Milk and owned almost 20% of the company. Freedom Foods even made a takeover attempt to buy all of a2 Milk in partnership with a U.S. Foods business.

But then the milk turned sour. After the takeover attempt failed the relationship between the two businesses deteriorated. Despite presumably loving the long-term outlook for a2 Milk just a few months prior, Freedom sold all 117 million shares in a huff in two tranches for A$70c and A$85c each in October and November 2015 – coincidentally right around the time that I was buying. All told Freedom Foods received A$93 million for their stake.

Today that stake would be worth over A$2.1 billion dollars. Freedom Foods had left over A$2 billion dollars sitting on the table. To put that into perspective, the entire market cap of Freedom Foods, a 30 year old company, is today only A$1.2 billion. Ouch.

That transaction was also a great reminder to always do your own deep research, and never automatically assume that you’re wrong just because somebody else has sold. Even if they are a knowledgeable strategic investor in the same industry.

What’s next?

This strong and enduring fundamental growth has proven even more valuable during the current crisis as a2 Milk again demonstrated its resilience. When Chinese mums became more concerned about the health of their little ones than usual, they stocked up on a2 Milk.

Catching monsters is hard. Our view of the future is cloudy at best. A2 Milk has proven incredibly resilient during the early phases of the current crisis, but this could always change in future. Or there could be supply disruption, or regulatory changes. Any number of potential bear theses always lie in wait, as usual. We must continually monitor for any changes in the company’s fortunes.

Above all the story of a2 Milk highlights that we should not spend too much time worrying about the general swings in the broader market when we could instead be doing deep fundamental research. When a business like a2 Milk increases its revenue by 1,000%, and its operating profits by 46,000% over five short years, then it matters very little whether the market goes up, down, or sideways.

Nothing is guaranteed, but if you can demonstrate those three qualities: vision, courage, and patience, you have a shot at aligning your portfolio with these incredible engines of wealth creation that I call monsters. The ride can be bumpy, but it’s also a heck of a lot of fun.

Disclosure: At the time of publishing Matt has a position in a2 Milk. Holdings are subject to change at any time. This report, and disclosure, should not be considered to be a recommendation.